I stepped back in time today and met what the West used to be. Unfortunately the homogenization of culture through the ubiquitous nature of technology means that most of these “real west†icons tend to be quite old, and tech-adverse. They are out of place in this age of smartphones, smart cars and smart drinks: kombucha and soymilk lattes.

Winter had come early to the Tobacco-Roots despite the date: October 30. I knew, because I was in them, cruising up this pass on ice under my 12 wheels. The remote mountain range that separated the Ruby Valley from that of the Madison River had only one pass over its 150 mile craggy length, and I had stopped at the top in a widened pull-off despite the howling subzero wind that carried blowing snow in windrift curvy stream patterns across the ice-streaked highway.

I was returning from our beef processor in Montana and had some 200 boxes of our fresh beef and pork to restock the webstore with. My 28-foot trailer had an insulated compartment up front, and that was where the beef was carefully stacked. The insulation would keep the beef from freezing on a day like this; in the summer it would keep it cold with the help of a little dry ice.

I don’t have much for OCD tendencies. I try to leave most of them for my wife and daughters. Sometimes, I frankly vex them for my lack of OCD. I tend to ignore a lot of details and just keep rolling along.

But trailer doors are a whole different thing.

One time, I forgot to drop the pin in my stock trailer door. It should have stayed closed, but a bump on the road or from within (big black 1000- pound steers have a way of bumping) popped the latch on the slider gate. Unpinned, it was free to slide.

I was only doing about 15 MPH on the curvy Idaho dirt. I remember thinking that I was a good driver, especially with trailers. I was a legendary trailer backer, after all. I had backed up towing rigs for literally miles on narrow mountain tracks when turnarounds were hard to come by. I knew what I was doing. I knew enough to always check those mirrors, for something going bad like a tire disintegrating.

And then black fur caught my eye. I focused on the big mirror on the driver’s side. It had a crack in it, but still offered a pretty good view.

I was right. There was a steer along the road. I instinctively slowed down. ‘Where did he come from?’ I thought. I didn’t remember seeing him emerging from the brush along the road as I passed by. And I rarely miss things like that. It bothered me. It should have really bothered me. But the bother was only mild at this point.

But I did have enough bother to slow down some more.

And then, I saw another one! Now there were two along the road! How could I miss them?

Finally, a flicker, a light bulb, one of those old Edison types with the clear glass stopping and starting as if the power was trying to come back on. It was in my brain, and it was an idea taking shape. And then, it went to full-fledged alarm bells when I saw another steer, this one bucking with glee, tail up in the air running for the other two.

Yep. You figured it out, dear reader. They were jumping out of my trailer! The gate was open! Too bad I didn’t have the likes of you riding shotgun!

It took me most of the day, but I managed to get all those happy wayward steers back in the trailer again and finally home.

So since then, I have become quite OCD about trailers. I will check and recheck those latches to the point of pulling over, out of 60 miles an hour, to recheck again. And my cooler door on my trailer is one of the targets of my new-found OCD tendencies. That one needs special care, because you need to hear the latch pop. Then you are good to go.

One dear gentleman in our employ had a load of fresh beef in there on a wintry night a few years ago. When he arrived at the freezer, I noted that the door was cracked open.

“Hey Bill.†I motioned to him to come back and look at the door. “I think this door came open. Any chance you could’ve lost some boxes along that curvy river road?â€

“Probably not.†He looked in. “Nope. I think it’s all here.â€

Over the next few days, I got quite a few phone calls from good folks scattered around the mountain river country of Central Idaho. Some of the I knew, some I didn’t. They went like this:

“Hey, are you Glenn?â€

“Sure am.â€

“So the wife and I were driving home last night along the river road, and on one of those 15 mile-an-hour curves, we found 3 cardboard boxes of beef laying there in the snow.â€

“What? No kidding?â€

“No kidding. Well, we thought we’d better grab them, ‘cause if we didn’t, the snowplow would just shoot them out into the river. And that ain’t no dang good. And then we saw your phone number and name on the box, and so we just figured we’d give you a call. You can come get ‘em anytime. We got them in the barn, just sitting here. Figured with the below zero we’ve been having they’d be still fine.â€

And so, I gathered beef from the four winds. Our beef. Bill is now more OCD than before. That’s good. Because a box of filet mignon can easily fetch $1000. Oh, the pain…

He checks gates, latches, straps. All it takes is once for most of us. Boxes scattered across the county, cattle with tails up, bucking, and even one time, we had a fine young man (nameless here) lose an old Honda four-wheel drive red (yep, red) ATV on that river road. (Never found it, and still living that one down. I hope he doesn’t read this.)

Embarrassing, perhaps. But in my ADHD/ADD lapses back to my childhood (I grew up before the likes of Ritalin, and as a result spent many afternoons in the principal’s office—and writing thousands of lines—‘I will not act out in class…’), I can occasionally miss stuff. And it takes a little embarrassment to get the system of OCD-like mind over matter checklists to get through life without loss of cattle, boxes, or Hondas.

So that’s why I rolled to a stop despite the Arctic conditions, and now, we can get to the heart of our story. Un-named pass, the only one over the jagged spine of Tobacco-Roots. Got to go out to check the cargo door. Again. There was some bad frost-heaves in the road back there. Black T-shirt flapping in wind, frostbite imminent, sun partly obscured by frozen ice crystal fog, leave diesel Powerstroke purring (don’t want gelled fuel).

Door solid. Latch clicked. Yes.

And then I saw him.

On horseback in the blowing snow distance of sagebrush: a man, horseback, with about 5 pairs of black cows, strays he had found on the range that icy morning. Frosty fur. Clouds of breath ripped away, horizontal by incessant wind. They needed to get in, to home to the ranch; the grass was buried under snow, and winter had set in up here, high up in the mountains. Summer was over. Bang. The window of warm air had slammed shut. Subzero filled the ranges.

As I watched in the wind from across the highway and a hundred yards away, there was a snow-drifted-in set of aging pole corrals, and he had reached the threshold of the gate with them. The cows knew that it was a little shelter, and they also likely knew it was the bus stop for a ride home back to the valley far below—and a hay pile.

So they calmly entered the corral, and cowboy closed the pole gate behind them.

I scanned the horizon for pickup and trailer that would be his ride out of this windblown snow-desert at 7000 feet. Nothing.

And I began to run. In black T-shirt toward the guy and horse, in the blowing and drifting, across highway. I wanted to catch him before he started back.

As I got up to him, I waved, and he waited. I got up to him close, and yelled at him in the wind: “Where’s your outfit? Virgnia City way? I’ll give you a ride.â€

He nodded, his wrinkled and sunbeaten cheeks now betraying a little color: red blood vessels spider webbed his face to keep it from freezing. It was the only skin exposed, wedged between a tattered silk scarf and battered cowboy hat. He had a thick and dirt-crusted hat liner over his ears, and that was good; otherwise, I think his ears would be that deathly white that frostbite makes.

“You with the Bar 7?†he yelled back.

“No sir.â€

“Well then who you with?â€

“I’m with me. I’m from Idaho. Was loaded with fat cattle, and now I’m empty. We could take your gelding and throw him in on board. I’m headed to Virginia City. You parked there?â€

It was about 10 miles down the other side of the pass.

He nodded, and we crossed the highway together, him leading his tall black gelding with tarnished silver bitted bridle, coiled and well used lariat on saddle worn smooth, carved flowering long gone and faded.

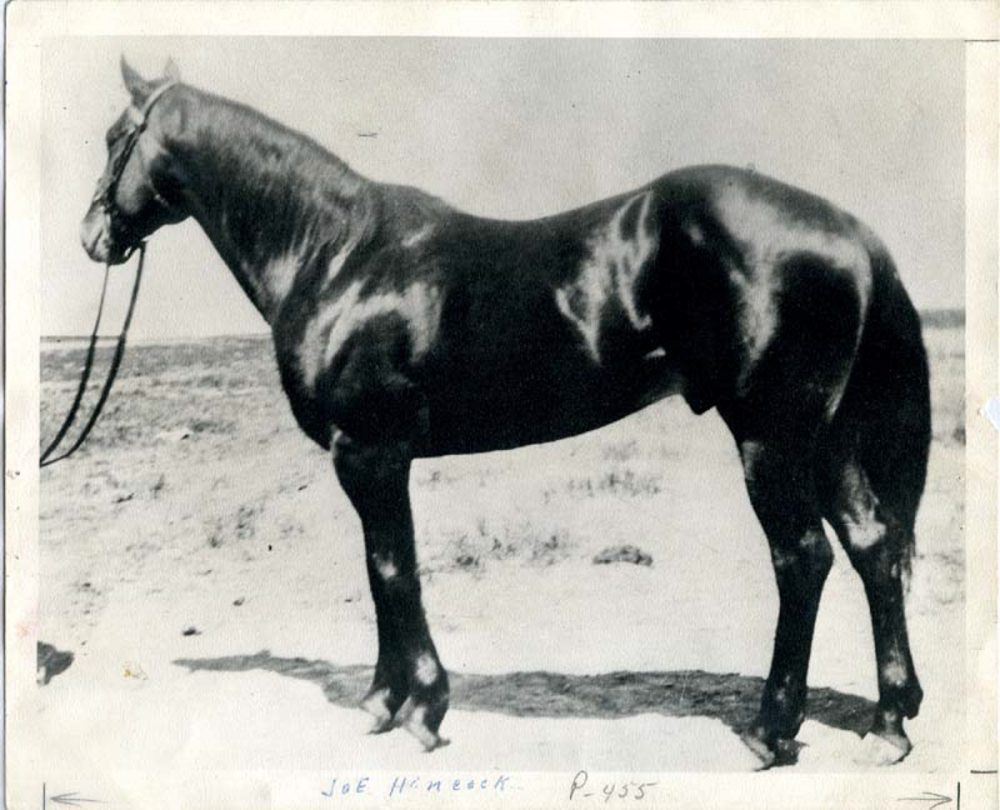

I threw open the trailer gate for him, and he nimbly leapt up in the back, and gelding followed. I watched as horse stepped up. He was a kind we don’t see very often anymore; he was of a Hancock type Quarter-horse body type; tall, and solid boned. He was the way horses used to be bred in much of the intermountain West; they were longer legged horses—made to travel long mileages in big rolling country. Gritty and tougher than many of the pasty horses of today.

I clicked the gate shut after the old boy jumped down, and double checked the latch. Good to go. Cowboy walked behind me as I headed for the passenger side to clear him a spot. My bedroll and down jacket are always on hand there in case I get stranded at this time of year (you never know when you’re going to have to spend the night, and on many of these roads, I’ll not pass anyone for several hours).

Cowboy yelled at my backside in the wind. “Don’t go though no trouble for me. I’ll be plum happy here in the pickup bed. I don’t mind a bit.â€

I turned around and looked him over. His clothes were torn and threadbare, but a layered combination of leather and wool. It was the same weather-wise combination people had been wearing for centuries; it had stood the test of time—of survival. He had on him no Patagonia microfleece, Gore-tex or North Face down jacket. Only layers—made of animal hides—wool and leather–and silk. Only his face was exposed, but he had earned his own form of leather there.

I turned around and grinned at him and yelled back, as I opened the door. “Nothin’ doing, pardner! No trouble at all.â€

He jumped in, grateful. I got in the other side, and closed the door on the driving wind. It was warm inside.

I reached over and put out my hand. “Glenn Elzinga. Salmon, Idaho.â€

He took off his thick mittens and grabbed my hand. “Buck Wilson. Twin Bridges.â€

His hand was rough as sandpaper, but warm. His eyes crinkled as he lightly cracked a grin in gratitude for the heat and a ride. He must have been in his late 70s, or perhaps even 80s. He pulled off his battered cowboy hat and liner. He would be able to hear now, and we talked. He pointed as he described where he rode, and where other strays might be in thick islands of timber, hunkered down out of the wind.

I told him I could relate. We’d been there, searching for strays in the cold, in as late as December.

“You got them all back?†he asked.

“Yep. We sure do. We’ve done our counts and are clean on our ranges. This year.â€

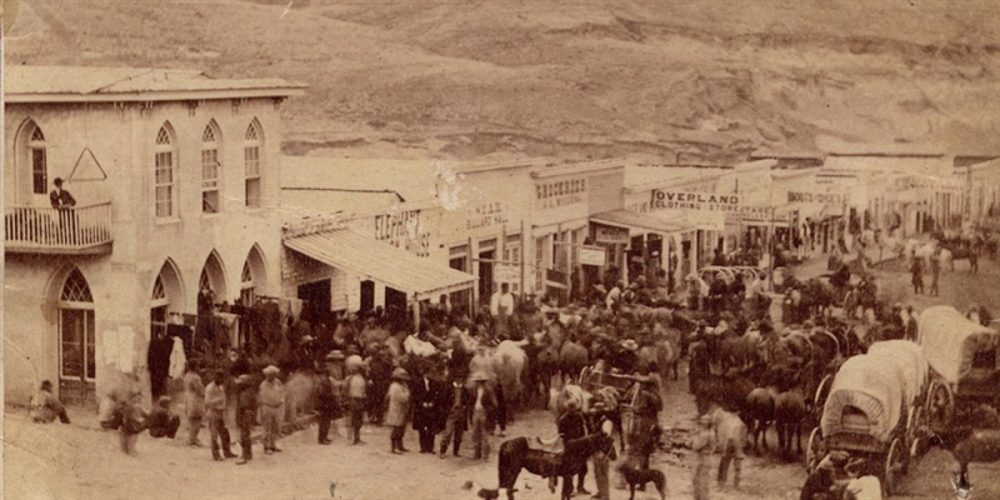

We rolled into Virginia City, county seat of Madison County. It was largely a ghost town and now practically a museum. It had sported a population of 5000 gold seekers in 1863, when it was still part of the Idaho territory. In just a few short years, $30 million (1860 dollars) was extracted in the yellow mineral from Alder Creek, the tiny stream I had been following with Buck off the pass. Then, the Idaho-Montana border slid southward to where the current one is, and the Montana territory was declared. Virginia City was the capital for a time.

Until gold—the driver of settlement, booms, and busts–was discovered in Last Chance Gulch, in Helena, Montana. Several thousand miners pulled up stakes and moved within a few weeks.

Now, Virginia City has a solid population of 200 souls. About 200 buildings remain from the original 1200. Over half a million visitors a year visit the old town, poking around through the old buildings and period architecture.

Some of them were here today; our descent had brought us out of the wind and ground blizzard, and the shelter of Virginia City made the sun feel warm. Occasional tourists dotted the boardwalks along the old false-fronted structures. I rolled down the window.

Buck pointed ahead to an abandoned hotel. “Right up there is fine. My outfit is just up the hill behind the Courthouse.â€

I pulled up ’97 pickup dragging 28-foot trailer, and jumped out, and got the gate for Buck to retrieve his old-style gelding quarter horse. I noticed the black horse was sharp shod; he had metal bars, or calks welded to his shoes to prevent slipping on snow or ice. Buck knew by life on the land. He had been riding this country for the most of a century. And it showed.

He reached out his hand, before putting mitten back on. “How much do I owe you?â€

I shook his hand, patted him on the back, and smiled. He nodded in reply, his eyes speaking gratitude. It was all we needed. He turned to his horse; I to my truck.

In the mirror, I watched Buck mount. Immediately he got the attention of a few tourists and their phone-cameras. Whether or not they thought he was the real deal didn’t matter (he was). But they saw him as museum piece; he blended directly into the historical landscape quite elegantly as he rode his tall black up the streets.

Buck cared not. Instead, he tipped his hat to each of them in the cowboy gentlemanly way that his forebears had before him.

Although men and women like Buck were commonplace as little as 40 years ago (I knew many of them), they are disappearing. They lived on the land and had become part of it. Now, it seems as though we’ve developed this sort of insulation from the elements, the dirt, the surviving of life on the land. It was an intertwinement, a sort of marriage we’ve always had in human history until now. We drive in heated or air- conditioned cars, airplanes. We watch the world outside over TV screens, and on Instagram via “reality†shows.

It’s been a slow change for humanity, taking a few generations, much like that frog in ever increasingly hot water. We’ve lost touch with our landscapes, our terra-firma. There’s not many Bucks left, and although not all of us are cut from the same mold as the likes of him, we still got fresh air in our lungs, clean water in our bodies, and maybe some dirt under our fingernails. And it is each of us that is responsible to ourselves and our loved ones to live and interact with our real—not contrived environments.

So go outside, friend. And breathe, see, listen, feel, and smell the landscape.

Happy Trails as you do.