Dear Friends and Partners

As we made our way through the switchbacks cut into the rock pasted against the cliffy bluffs, the crystal clarity of the Salmon River rolled lazily by below. An orange sun worked its way down to the horizon. Like us, I think the sun may be getting tired of forest fire smoke. The fires keep going into this month of September–yes, this is the one we have been looking forward to since July, because it is by now that we usually find ourselves free from smoke.

But this year, the driest year ever in recorded history, it is not to be. I looked in my rearview mirror of our 4-wheel drive truck; a plume of powder dry volcanic ash dust lifted lazily skyward, and then was swept away by the persistent breeze. Caryl and I are taking a drive up to our upper ranch–the 700 acre Little Hat Ranch. It’s up in the mountain foothills, surrounded by our grazing country. It’s about a 45 minute drive from headquarters.

We were heading up a more than a little hopeless; the drought was taking its toll on more than the grasslands—even the wildlife was likely to pay a price. We were about to verify if indeed that was the case.

The 7 inches of annual precipitation we normally get along the Salmon River breaks was more like a stingy 3 so far this year. So much of the bunchgrasses we depend on for summer forage never grew, and we actually had to skip the cattle quickly across the country in search of better grazing up high (we found it). The cured out seedheads that dotted the low hills were last year’s, still persistent, as no heavy snowfall knocked them to the ground.

“Hey–what’s with that greasewood?” I point out my window at the low desert shrub typical of the dry wash of the gulch out my driver’s side window. I turn quickly to my resident plant ecologist (Dr. Caryl Elzinga, in some circles). “It’s a lighter color than I’ve ever seen it.”

“Yep. It is dropping many of its leaves.” She says. Moisture conservation. Sagebrush does it as well when times get tough. Most the plants here have mechanisms that carry them through the driest of dry. We call it the low desert. It’s the hottest, most extremely brittle part of our grazing range. These habitats have scorpions, lizards and rattlesnakes that slither through cacti and saltbrush.

It’s ironic that on the very same 70 square miles is another extreme: alpine tundra. There, on the shoulder of Taylor Mountain, nearly 6000 feet higher in elevation, just 14 miles distant, grows arctic vegetation above treeline in an environment characterized by deep winter snows and long periods of subzero temperatures. Even in this hot and dry year, there has already been snowfall there in as early as 2 weeks ago, in August. Winter is coming soon to Taylor.

But not so in the lowlands; hot and heat are still the order of the day. As we make our way through the broken and scabby hills, we spot unlikely welcome sights along the way: the rabbitbrush is blooming a riotous golden yellow more than we’ve ever seen it before. Hillsides are nearly iridescently golden with the show. Who knew that in the driest year, Chrysothamnus would bloom a storm of yellow

Then, Caryl spots green grass. One inch high, emerging from the base of a rattling, shaking-in-the-wind skeleton of bluebunch wheatgrass. It’s opportunistic fall grass that decided to make the attempt to gather a little sunlight, made possible by a freak afternoon thunderstorm that dumped a 1-hour downpour on some of the range about 4 weeks ago. We could see the gray and windswept vergas curtains of rain falling on this particular spot in the low country from headquarters, over 10 miles away on that day in August

We summit Little Hat Pass, and start down the sweeping curves that lead to Little Hat Ranch. Little Hat was homesteaded sometime around 120 years ago; what information we gather about the remote outpost was that the first white settler arrived there somewhere around 1880

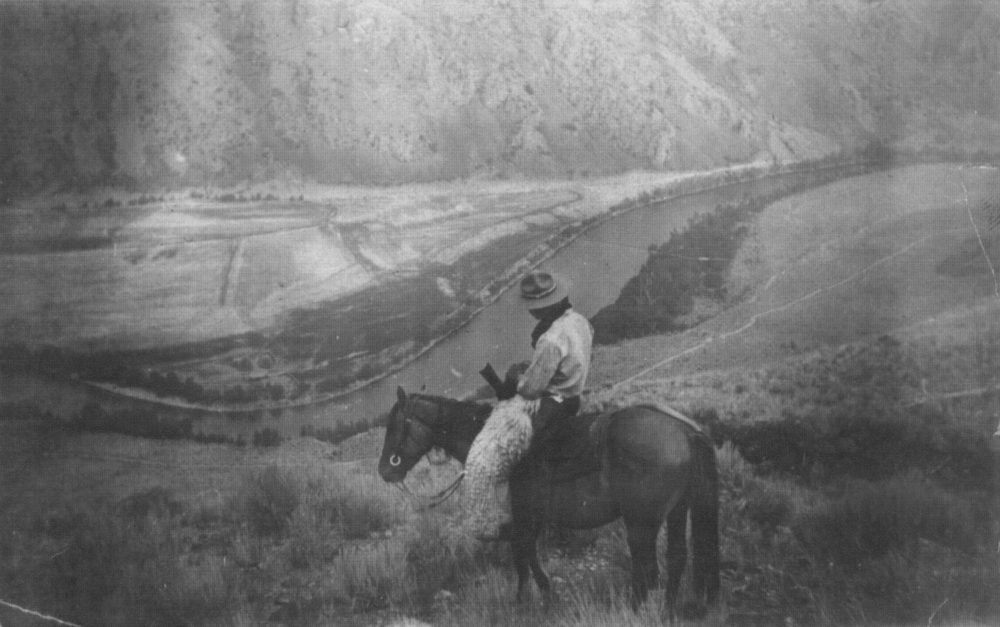

We have a few black and white pictures of the ranch taken around 1917. They depict the first known owner of Little Hat–at notorious outlaw cattle rustler by the name of Virgil Williams, mounted on a hardscrabble horse with the tools of his trade: a lever action saddle rifle and six-shooter. He wears sheepskin wolly chaps to keep warm despite brisk weather along the breaks; after all, a self-respecting stealer of the neighbor’s cattle needs to ride horseback in rain, snow or shine.

And it gets cold when your occupation has you often riding at night.

Another image shows the condition of the ranch itself along the banks of Little Hat Creek. The creek bisects the ranch with about 2.5 miles of bubbling riffle. Although the viewer can easily determine exactly where the photograph was taken from by locating the characteristic rimrock about the valley bottom, the image is thoroughly unsettling to someone familiar with the ranch and the creek as it is today.

It’s because in 1917, there is vitually no vegetation in the picture along the valley bottom except some bedraggled looking willows. There’s no cottonwoods, aspen, birches or alders. There’s hardly even any grass. There’s just a few dots of sagebrush scattered throughout the view, along with the herd of horses that I am guessing are partly responsible for the demise of all things green. No; I’m wrong; as it always is, it is not the horse or the cow, but the person who owns them.

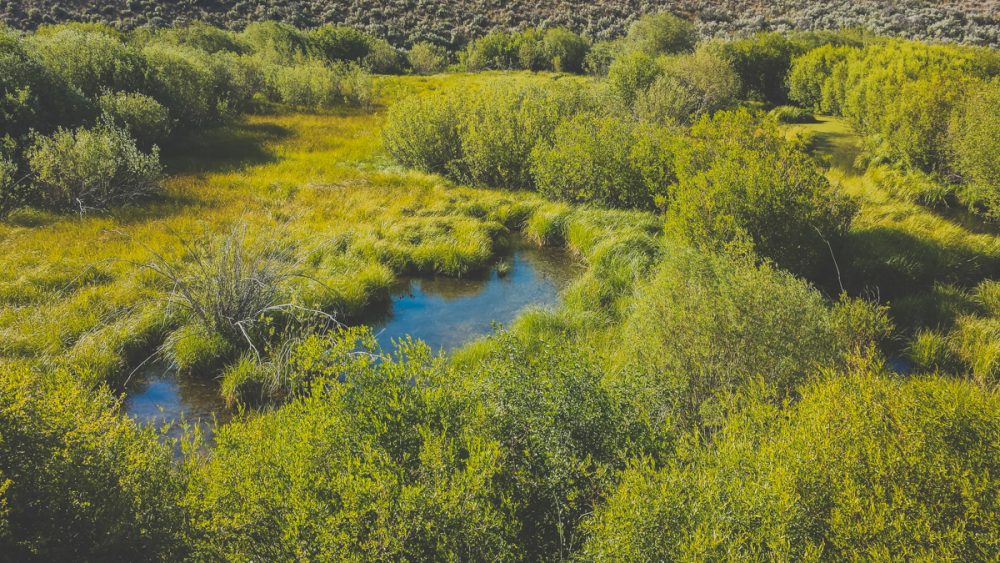

Now, in 2021, the creek is the center of life in this part of the range. It’s because it teems with squishy-underfoot lush green meadows, tall rustling-in-the-breeze cottonwoods, impenetrable copses of willow and birch, and a veritable fruit farm of wild currants and rosehips. We used to be able to ride horseback anywhere on the ranch through the sparse willow brush, at least still hanging on despite 100 years of continous cow grazing. When we got it in 2005, the willows were at least there. It had improved somewhat since Virgil’s ruthless-on-vegetation era.

But today, nearly all of the creek is “armored” with the steel of tangled woody plants. It’s because we switched from a continuous grazing model to one of high intensity short duration. We began grazing the ranch in super short bursts. Now, we’ll put over 400 head on there for as little as 2-3 days, where before cows grazed 24/7, 365.

And when we made that change, we unknowingly rolled out an invitation to a new business partner. We needed someone who could dramatically move the needle of change to the next level.

And the relative of rat responded. You probably figured it out; we needed beavers. With their dam (“damn!” to some haters of them) building projects, they could create more wet meadows, hold back water, create more fish habitat, and keep the ranch greener–longer.

And that was why Caryl and I were heading up to Little Hat on this September day. We wanted to see how they were faring; the last time I looked, I didn’t see any fresh dam work. I became very concerned. If you don’t see freshly cut willow branches and regularly maintained earthworks, either Mr. Beaver left, was eaten by a bear, or was shot by a bored hunter (beavers, for most people are thought to be a menace as their earthworks have been known to flood roads by blocking culverts and even damage homes). Our hunter friend likely smiled when he lowered his gun and beaver lies bleeding, thinking he did humankind justice against the rogue rodent that day.

But as you likely figured out, dear reader, we think differently about Castor canadensis. We see them as perfect partners in regenerative restoration. And that benefits even us, as ranchers–the harvesters of grass. Because where there is more water, there is more grass.

On a place like Little Hat, they’ve probably been missing for over a hundred years, handily extirpated by trap and gun. The first rodent removers were fur trappers of the 1800s, and then again by early ranchers mistakenly thinking that beavers were stealing irrigation water (in fact, their impoundments have been shown to effectively store it for the dry part of the year).

The wind had died to a murmur as I hiked up the trail along the creek; I left Caryl alone back at the road junction which was also the end of the road for our 4 wheel drive due to roads that went rogue, becoming trails with rockfall and brush. She would botanize there, while I did my power walk recon mission. The sun was already down, and I still wanted to cover about 3 to 4 miles to search for The Beave. The trail used to be the old road through Little Hat–it was the only conduit for supplies twice a year for the tiny colonies of humans that lived in the high and remote Hat Creek country. The road since fell into disrepair, probably during the 1940s, and since receives little to no use.

I looked at the creek channel where I could spot it on the way up the valley. Drought had taken its toll. Much of it had was now mud puddles or worse, a dry creek bed. Without rainfall this year or adequate snowmelt this spring, there was no water left. It had simply run out of the system. The plants were OK, because the entire wetland corridor had good vegetation cover that protected the thick organic soil matrix underneath it all. It held literally millions of gallons hostage against the drought. That alone would keep the plants in the wet meadows alive.

I plodded onward, hopeless now. Without water in the creek, the beavers would have certainly left for another abode. Water was their security blanket. Top speed for a beaver was around 6 miles an hour overland. But they were astoundingly incredible swimmers, and could stay under for over 12 minutes. Between the depth of their ponds behind their dams, and their incredibly strong latticework lodges, they were secure from predators. But without water, they were literally like sitting ducks to the likes of bears, wolves, coyotes and mountain lions.

There was a good chance that my regenerative rodent partners were toast, a victim of drought.

I had Clyde, my inseparable border pup with me; he chased a cottontail here and there to no avail, and on one of his hopeless roundabouts, he scared something up down in the brush that sounded like a wooly mammoth on the rampage as it tore through the dense willow copse. I ran after the sound, hoping to put eyes on the instigator, but resisted the urge to get on all fours on the low game trails through the maze–I just had a mental picture of me on all fours and coming face to face with a big sow black bear or, worse, the bottom of an angry moose hoof sent as a painful message to my face. Not interested in such encounters of the close kind.

The crashing subsided as the critter got some distance from us, and we went on. In another moment, we came up on the first dams I recalled from my last visit. The tiniest trickle of water slipped out the bottom of the first dam. Both dam number one and two were sad affairs. No recent work had been done. The water level behind both had dropped by 6 inches, and was stagnant looking; there was no signs of recent movement in those waters.

At dam number 3, my eyes found hope. Freshly cut willow sticks and neatly piled mud completed the matrix at the top of the perfect dam (not “damn,†mind you) structure. I was elated. In addition, I spotted newly submerged bluegrass flats that I noticed last time were getting clipped to golf-course level by elk that frequented the ranch in the fall in search of green. Their sign was everywhere and their teeth could readily graze the short grass. But now, that grass was underwater. And that meant that the water level rose in just the past week.

As I headed upstream, I got to the big impoundments; there, thousands of square feet of pond area still remained. Inlets and bayous formed an amoeba-shaped pond that stretched across the entire valley bottom. As I hiked further up and in, a nearly continous chain of ponds reached up to Little Hat Canyon. Here, the creek was continous, and still alive, thanks to the storage engineers. Walking along the creek and ponds, I could feel by the spongy nature of the soil I walked on that the storage went far beyond that in ponds.

It was a desert oasis. A drought stronghold. Here, I saw life in the waters. Depths of over 2 or 3 feet could be seen, and I knew that this refuge was where all the aquatic critters had ended up. The fish were safe here; frogs plopped in from the edges as I walked by them. Here, they would even find safety in the coming winter. And the beavers themselves would be safe from the teeth of canine or cat.

Ironic that caretaker of them all was a rodent with long teeth; the very same that men did all they could do to extirpate. Without them, we couldn’t have had the hope for a lot of the wild habitat residents who would die from the dry. We didn’t even know the drought was coming. But changing the paradigm by which we managed our cows about 7 years ago created hope for the entire food chain—what biologists call the trophic cascade—by inviting beavers back into the scene.

All we had to do was mimic nature; every wild animal we observe grazes and feeds in areas non-continuously. Recent telemetry studies on bison, deer and elk in our Rocky Mountain area show that they travel and range over thousands of miles. Even predators like the mountain lion and wolf travel in the high hundreds of miles over the course of a season.

We just needed to adopt that same vision; and now, we graze with the “just passing through†mentality. And it has changed everything.

Happy Trails.